“The Industry Is On Rolling Racks”: The Rise and Fall of Hong Kong’s Denim Industry

In 1970, Hong Kong was coming off a decade-long economic boom, transforming from a small British colonial outpost to an international city, with high rises taking over the skyline. An influx of businessmen and refugees from Communist China in the 1950s had swelled the population, turning it into a busy manufacturing port. So much so that three different textile mills were set up after World War II by unrelated men who shared the surname Lau.

As one observer wrote, “When I arrived in the territory in 1970, Hong Kong’s reputation was as a low-cost manufacturer of cheap clothing, wigs, plastic goods and toys.”

That year, Johnnie Lau founded the denim mill Mou Fung Limited. It was just 10,000 square feet containing 49 sets of shuttle looms. But Mou Fung would grow both in size and reputation, alongside Hong Kong, to be a respected global leader in the denim industry, eventually manufacturing quality denim for brands as diverse as The Gap, Old Navy, Uniqlo, Armani, American Eagle Outfitters, and Calvin Klein.

In 2023, when Mou Fung finally shut its doors, it was one of the last denim mills owned by native Hong Kong citizens, and the last of the Laus still doing textiles in Hong Kong. Its rise and fall has more to say about the fickle nature of today’s fashion industry than it does about the business acumen and skill of the Lau family. In fact, it’s impressive it lasted this long.

The arc of fashion history bends toward cheaper production.

Denim Gets Interesting

When Mou Fung was founded, denim was getting an upgrade. Long seen as workman’s wear, and then a symbol of the counterculture, designers were taking an interest. In 1976, Calvin Klein was the first designer to show blue jeans on the runway, followed by Gloria Vanderbilt’s hit jeans in 1979, according to Vogue. Along with basic, traditional indigo-blue denim, Italy started making fashion denim fabric for things like dresses and skirts, plus striped denims and other new styles.

Kingpins founder Andrew Olah was working as a marketer and agent in Canada, and would drop by the Lau’s house in Canada, where he met Johnnie’s kids, Raymond and Georgianna. The brand Olah was sourcing for, Brittania, was manufacturing denim in Hong Kong using cheaper Hong Kong denim, and growing at a breakneck pace. American denim mills, to their detriment, did not see a future in new forms of denim and would only create basic denims.

Olah says most Hong Kong denim mills were cheap, quick, and experimental. They “could do anything,” he says. “Striped denim, checked denim, jacquard denims, black denim, grey denim, whatever you want. I mean, they were very flexible and they had small minimums, and they were just really quick.”

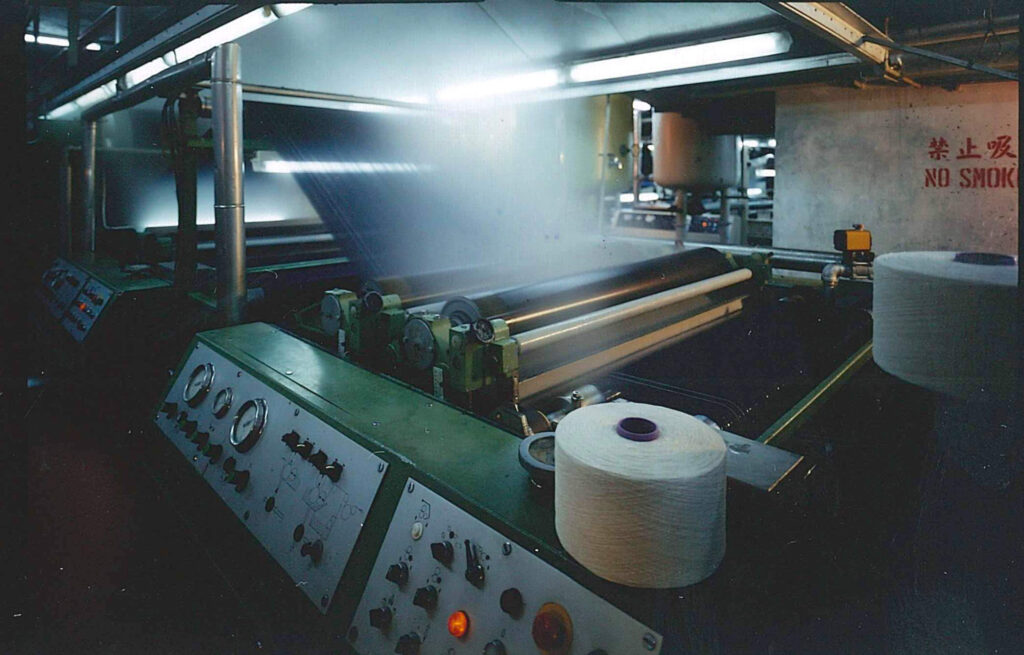

Johnnie was well positioned to benefit from this collision of economic development and fashion’s taste for interesting denim. He imported Swiss weaving machines, and was the first in Hong Kong to offer rope dying in 1976, which gave large brands the consistency of color they were looking for in large orders, securing Mou Fung’s reputation as the highest quality and most trustworthy mill.

Mou Fung was also one of the first mills worldwide to use reduced solution indigo in 2000, when the respected dye company BASF offered it to Mou Fung to try. The traditional synthetic indigo dyeing process requires workers to cut open bags of powdered indigo and add them to the equipment for mixing, creating a situation where they can breathe in concentrated aniline and whatever else is in the indigo dye powder. Liquid indigo also uses less water, and creates a higher quality denim. (A majority of Chinese mills still use powder indigo today.)

“My dad’s philosophy was always use the best for machinery,” says Raymond Lau. He remembers hearing (perhaps apocryphal) tales about importing the rope-dye machines from Morrison in South Carolina. “I heard stories that they bought it from Morrison and flew the engineer over,” he says. “Even the Morrison engineer couldn’t start the machine; he locked himself in the hotel for three days because he couldn’t get the machine to start. They figured it out eventually.”

Johnnie’s wife Rosemary served as the company’s accountant. “Back in the 70s, I remember when we would always hang out in the office on the weekend — they worked 7 days a week,” Raymond says. “We would climb up to the row of fabrics and jump up and down.”

Detailed and organized, Johnnie could afford to charge more and be picky about his clients, working with hot brands like Jordache, Levi’s, Wrangler, and Pepe. “Johnnie was always sold out,” Olah says. “He was always very tough to get into. And he was a wise, smart businessman.”

“He was the best in that area. Absolute best,” Olah says.

Moving to the Mainland

By the early 1990s, prices in Hong Kong for manufacturing were no longer competitive with other producers in Southeast Asia, and office space was some of the priciest in the world. Plus, China had imposed policies that stemmed the flow of cheap labor from the mainland. Many manufacturers started building in mainland China.

“In the 90s, they had no environmental regulations, no labor laws,” Raymond says of China. The mainland, Hong Kong-owned mills could charge less, and the Chinese-owned mainland mills could charge even less than that. They got cheaper as they moved north to newly industrialized areas.

At that time, says Sven Doerbecker, a product manager at Ahlers P.C., Pierre Cardin’s biggest licensee for sportswear and denim, most denim brands weren’t working with factories in eastern Asia. (Doerbecker’s father, who passed away last year, worked with Mou Fung for 30 years.) Levi’s still did its own manufacturing in the U.S., for example, and a lot of denim for European brands came from Italy.

But Ahlers had set up its own denim laundry in Sri Lanka, so was open to sourcing from Asian mills. It found Mou Fung through word of mouth (likely from Esprit) and started putting in orders of denim to ship to its Sri Lanka laundry. Mou Fung was able to do stretch denim, and at a lower price than Italy. Sixty percent of that denim, a casual style for middle aged men “at the football stadium,” Doerbecker says, ended up coming from Mou Fung. (That denim is still in the Cardin collection; it’s now produced in India.)

According to the International Monetary Fund, by 1997 Hong Kong had transformed itself into a global center for trade, business, and finance. With 6.4 million people living on an island a third larger than New York City, it was the world’s seventh largest trading entity, and the world’s busiest container port. And with a per capital GDP of $24,500, it outmatched Australia and Ireland in terms of prosperity.

Sven Doerbecker first visited Hong Kong and the Mou Fung team in 2005. They would get picked up at the airport and brought to the Mou Fung building in Hong Kong, an old, tall, light blue building which looked like it was bleeding indigo. There was no grand entrance, and the same lady operating the elevator was always there, asking guests which floor they were going to. The looms on the floor above shook the office. “They knew what they were doing, they didn’t care about whether the entrance was really well designed,” Doerbecker says. “That’s also the way we work, that’s why it fit so well.”

In 2006, Mou Fung finally invested $24 million in a 200-acre, vertically-integrated plant in Zhujai, in mainland China, which could produce over 25 million yards of denim fabrics. It was the last Hong Kong mill to make the move.

“We have the machinery, but what’s been missing is the taste and design,” Raymond Lau, who was stepping into a leadership role, told the Wall Street Journal. His sister Georgianna had joined to lead sales a few years earlier. He added that he was directing his designers to follow trends more closely. The marketing and product design remained in their Hong Kong building.

But China’s local environmental and labor regulations were always changing, often without warning, making it hard for Mou Fung to plan ahead and operate as efficiently as it had in Hong Kong.

It’s Always About the Prices

Around that time, Hong Kong and Chinese denim received its next major blow. As Bangladesh’s ready-made garment manufacturing industry burgeoned, brands started to look to South Asia — India and Pakistan — for sourcing cheaper denim fabric. The end of the Multi-Fiber Arrangement in 2005 and Europe’s preferential tariff treatment of Bangladesh shifted the locus of the industry further.

“Once Bangladesh got free trade status, that was the moment Hong Kong denim was in trouble,” Olah says. The Gap, which had dominated denim trade in East Asia, started sourcing from India. Mou Fung’s quality and goodwill could only protect them up until the 2010s. Even the luxury brands, despite charging so much more to consumers for luxury branded denim, would only pay Mou Fung a little bit more.

“For seven, eight years it was getting more and more expensive compared to Pakistan, Bangladesh, India,” Doerbecker says. Ahlers continued to work with Mou Fung despite price increases. “We paid a little more for the reliability and trust,” Doerbecker says. “We worked so long together, we were like a couple. We really understood each other.”

Eventually, about five years ago, Ahler’s started sourcing part of its denim fabric from India. Other brands were making the same choice, despite Mou Fung’s sustainability credentials.

“It’s always about prices,” Doerbecker says. “We try to do our best with sustainability, but it’s frustrating. The customer doesn’t care. You do it for yourself, but in the end, you need to make money.”

As the Transformers Foundation has reported, brands have been asking for more pricey sustainability initiatives, credentials, audits and certifications, but won’t pay for them. “What is always the biggest challenge to us, to balance the cost of all environment-friendly raw materials and a sustainable production process,” Raymond told Fibre2Fashion in 2019. “Somehow no one is willing to pay extra to save the world.”

Raymond told Fibre2Fashion the family was hoping to come back from a tough two years and get production back on track, perhaps by focusing on higher end boutique brands or Russian and Chinese brands.

“The industry started from a little cough [and went] to getting really sick,” Georgianna wrote by email. “This is also why we stopped our production after half a decade of blood and tears my parents had spent.”

Doerbecker’s last visit to Hong Kong was in November 2019. The trade war with China was full on. Then Covid happened.

“After so many years, I had to tell them,” Doerbecker said. “There was no other choice.”

The End of an Era

On Christmas Eve, 2022, Mou Fung posted a goodbye note on its website. “May I take this opportunity to thank you for all your support over the years and wish you all have the prosperous year of 2023.”

Production stopped months ago in the Mou Fung factory. The workers have been laid off, the machinery sold.

“It’s quite sad, honestly. It was full of machines a few years ago. And suddenly everything is gone,” Raymond says. Tellingly, every last bit of Mou Fung denim has been shipped off to a brand — none will become orphaned deadstock. “I saw the last batch ship out, and the warehouse in China is empty,” Raymond says. (He thinks it went to American Eagle.)

But that’s the way it goes in fashion, Olah says. Textiles can serve as a springboard for a developing country into high tech manufacturing and banking, and then fashion moves on to the next cheaper place. This story has played out in Japan, then Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, and Taiwan. Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam are in transition. And Bangladesh? Well, we will see.

“Our industry is literally on rolling racks,” Olah says. “The whole industry rolls to wherever is the most opportune place to be. It’s an evacuation. But at the same time, it also means that the society is doing a lot better. Yeah, there are better jobs than textile jobs.”

The Lau’s are looking for their next opportunity. But not in textiles. Georgianna is looking at vertical farming.

Doerbecker has more than a little nostalgia for the way the denim industry used to be. “Maybe it’s due to my age,” he says. “Relationships don’t have the same value as they had in the past.” Today, Doerbecker says he hasn’t met the owners of the factories Ahlers works with in India, and Ahlers must exert more control over the production process as a result.

“I looked forward to going there — Mou Fung and the others as well,” he says. “It was the glory days. Not any longer. But it’s good to know that I had it.”