Crespi D’Adda is unlike any other Italian village you’ve seen. Laid out on a neat grid reminiscent of a 1960s American suburb, the Italian-style homes, which used to house the employees of the cotton mill, get grander as they move south, culminating in the large villas for the upper management.

This World Unesco Heritage site is a popular day trip from Milan for Italians interested in the region’s rich textile history. It’s also a pleasant walk around the quiet town, its homes and gardens in various states of disrepair.

“It was the leader probably for 25 years, in Europe for sure, maybe in the world,” said Mauritzio Baldi, one of the premier denim designers in the world, who now works for Diamond Denim in Pakistan.

Elisabetta Benagli, who worked in sales for Legler from 1974 to 2007, points out the office in which she worked, inside the renovated headquarters of the cotton mill, which was originally built in the late 1800s.

“I used to come early, before I had to be in the office, just to have a walk. It was so refreshing.”

Now the brick smokestack leans precipitously over the road. The mill, with its star-shaped brickwork around the windows, is too dangerous to go inside. The clocktower behind the locked gate is stopped at 4:52 pm, the moment when the fate of this mill town, and, arguably, the fate of a textile dynasty stretching back to the 1700s, was sealed.

130 Years of Swiss-Italian Cotton

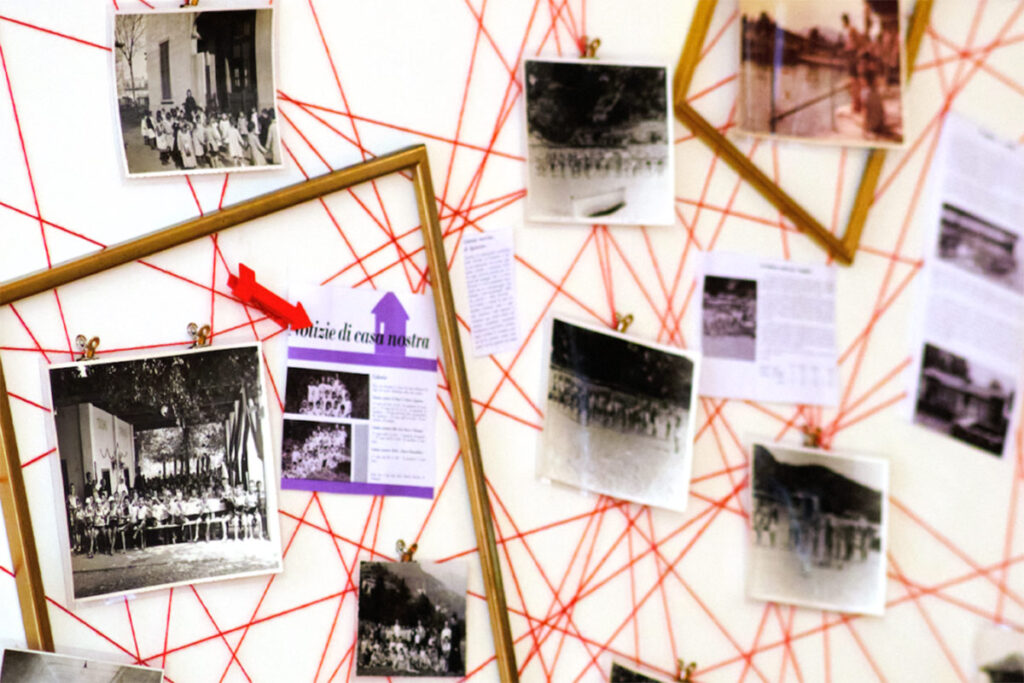

The Legler Foundation, housed in the former headquarters of the Legler textile firm, is putting on an event to celebrate Legler’s crucial role in Ponte San Pietro’s history. Middle-aged and elderly people, many of them former employees, peruse the exhibit of cotton fabric samples, plus marketing materials for something called Quikoton, a non-iron cotton from the 60s.

“This thing touched so many families,” said Marco Bonzanni, a respected denim professional who now works at Candiani Denim, looking around.

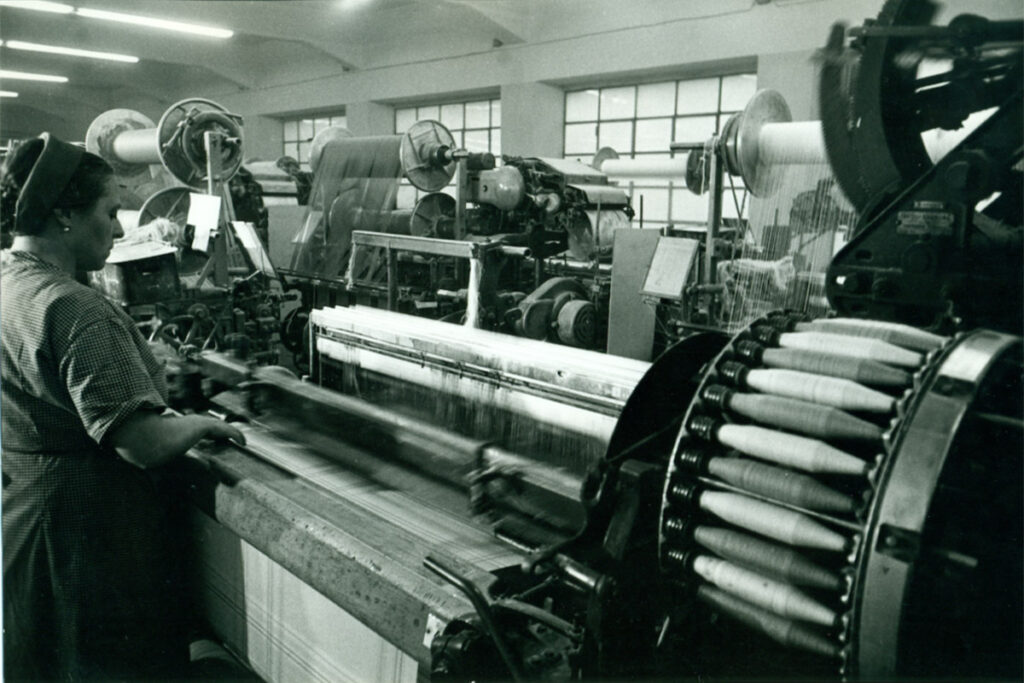

During speeches by the incoming mayor and a local economist, black-and-white footage plays behind them, showing the old factories running at full tilt. In one, a man inspects the bolts of cotton, while another man with a typewriter on wheels follows him to take notes. In another scene, young men pour steaming dye from buckets into old dye baths with cloth rollers.

It’s a rare day in which the public can enter the archives and get a tour. We dive into the library with rows of leatherbound books, then up the stairs to the old offices, where the tour guide opens up locked cabinets stuffed with rows of colorful mid-century fabric swatches. Binders are open on the tables, full of fashion ads and editorials featuring models wearing summer dresses using Legler cotton.

B y the time the Legler family set up shop in Ponte San Pietro, it had been in the business of cotton spinning and weaving in their home country of Switzerland since the 1730s, according to an Italian- language biography of Fredy Legler (1916-2002) published in 2021 by the Fondazione per la Storia Economica e Sociale Di Bergamo.

In the 1870s, the Legler cotton mill was outgrowing its hometown of Diesbach, a sleepy and small village in the Canton of Glarus. When Italy was unified in 1861 and imposed tariffs on imported textiles, the village of Ponte San Pietro outside of Milan beckoned. Swiss manufacturers had been in the Bergamo area since the 17th century, which was famous for its silks. Ponte San Pietro, about 9 kilometers away, population 2,700, had a rushing mountain river to provide power to a mill, a railway connection, proximity to Milan, and – familiar story – low wages.

So in September of 1875, Matteo Legler purchased land on the bank of the Brembo River just above the Ponte San Pietro railway crossing. Swiss technicians built the new factories in 1876. By 1887, Matteo had added a small dyeing and then bleaching department, and in 1894 built a small iron bridge over the river to connect the Legler buildings on either side.

From almost the beginning, the Legler family and its eponymous company were an example of a community-oriented business – at least, for its time. The Legler company built housing for employees, opened a Swiss school, contributed to the founding of a worker cooperative store where employees could get basics at below the market rate, and opened an old age and sickness fund for employees. In 1906, it had 1,600 workers: half of them women and 20 percent oft hem children. (Child labor laws weren’t instituted in Europe and America until the late 1930s.)

Matteo upgraded his company’s product from cheap calico and moleskin – a cotton fabric that is brushed to make it fuzzy – to higher-end cotton textiles like velvet, complex textile cut by hand that had a production cycle of 60 days.

In the 1910s, textile firms provided two-thirds of the employment in the Bergamo region. The Legler firm, guided by the second generation of the Swiss family, survived the financial crisis of 1907, both World Wars and the bombing of Bergamo’s factories, and recurring cotton shortages, to become famous for its quality cotton textiles.

In 1950, when it celebrated 75 years, Legler had 2,730 employees –– equal to the entire population of Pon San Pietro the year of its founding. By all accounts, it was a great place to work. Legler provided marriage and childbirth bonuses, subsidies for funerals and health services, subsidized housing, a retirement home, a kindergarten, an infirmary, sports equipment and courts, and education scholarships.

All was not perfect, of course. As at all textile companies, the mill produced cotton dust which can cause lung disease; the noise of the shuttle looms was deafening; and fumes pervaded the dye house. Still, employees often remained in the company for 30, 40, even 50 years, with multiple generations of the same family entering the firm – including the Leglers themselves.

Fredy Legler, the third generation, moved into management of the Italian firm in the 1950s, though he wasn’t handed the reigns until the mid-1960s. Fredy had his work cut out for him. The heyday of textile production in the Bergamo area was on the decline.

In September 1968, Fredy shared in a speech at the International Federation of Cotton and Allied Textile Industries a familiar complaint to those in the industry even today:

“It’s a fact that textiles really get bad press. This mediocre image reflects a vicious circle: the instability of the industry causes a general lack of trust, so that it risks attracting above all mediocre personnel, which, in turn, only increases this instability… If the textile industry were presented as a modern industry, up to date with the most modern techniques, and investing confidently in the future, much would be done to correct the current image, and young and capable managers could be attracted.”

His first big move was to convince French couture designers, including Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Balmain and Pierre Cardin, that Legler cotton was just as glamorous as silk for their dresses. Balmain and Cardin would frequently travel to Ponte San Pietro to discuss fabrics for the next season. The 1968 budget report said that 21 percent of Italian cotton exports were from Legler. That rose in the following years to a third of all cotton exports.

But with the upcoming renewal of the textile union labor contract in 1970, Legler faced higher labor costs. Making such small runs of all different types of cotton in all different prints and colors was inefficient. Fredy was looking for a way to simplify.

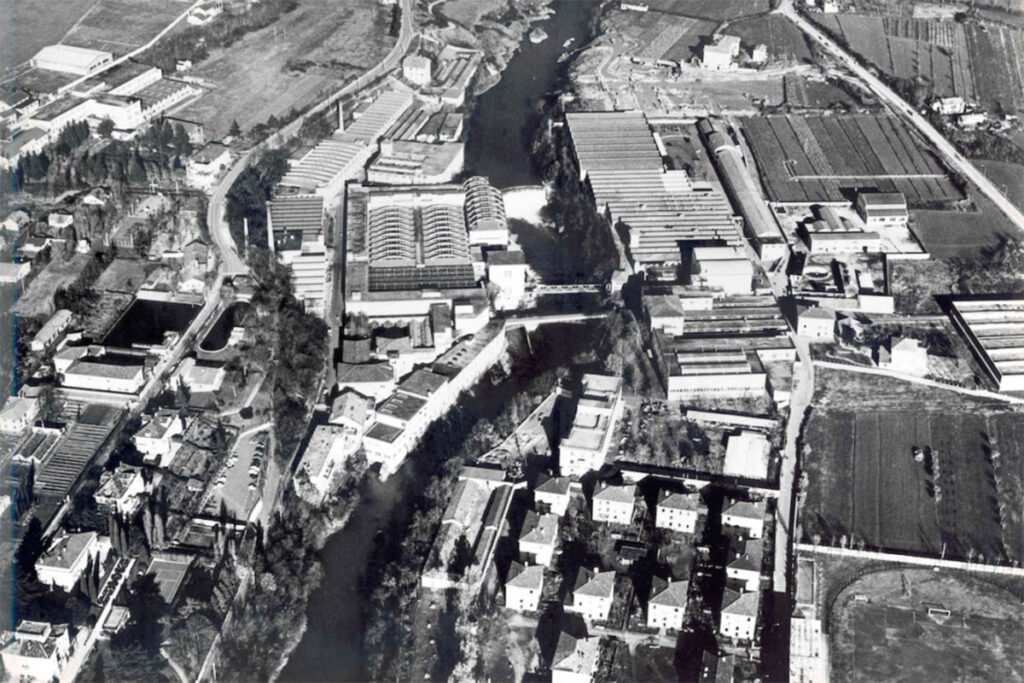

An aerial view of the factory Credit: Fondazione Legler

Denim to the Rescue

Denim was exploding in popularity in the United States, and that fervor had invaded Europe, leading American denim brands like Lee and Wrangler to open up cut-and-sew factories in Belgium and import denim fabric from the U.S.

Legler knew its cotton. But it would have to install new equipment to make the 150-centimeter-wide fabric (as opposed to the 90-centimeter-wide fabric it had been making) and to switch from jigger dyeing to continuous wide dyeing. The benefit to making it in Europe was that it would cut the shipping and tariff cost of importing denim by 25 percent.

Legler formed a partnership with an old cotton textile mill 14 kilometers away in Crespi d’Adda and called it Inditex (no relation to Zara). With the help of an American consultant, Legler set up a new factory system within nine months to dye and weave 15 million meters of blue denim. Raw fabric flowed from Crespi D’Adda to the finishing plants in Ponte San Pietro. By the beginning of 1972, Legler was shipping denim fabric to factories in Belgium, surprising the American brands with its speed and success, and making it one of the first denim mills in Europe. (Italdenim started shipping denim the same year.)

As more denim brands set up cut-and-sew factories in Europe, Legler expanded production. Turnover increased from 35 billion Lire in 1969 to 150 billion Lire in 1975. According to professor Giuseppe De Luca, president of the Legler Foundation, in the 1970s, Legler provided denim for a quarter of all jeans made in Europe.

“One of the main advantages of denim production by Legler was that it could supply the Belgium mills with a great quantity of denim of the same quality in one shot,” De Luca said. “So from the point of view of the producer, you have a reduction in the cost of negotiating with a lot of suppliers.”

Elisabetta Benagli joined right out of school in 1974, managing accounts first in Scandinavia and then in America. She had an apartment to live in during the week in Ponte San Pietro. In the morning, she would play tennis with another employee on the company courts. In the evening, clients and employees from all over the world – Germany, Japan – would gather in the kitchen for a meal and conversation. “I loved working for that company. I think I never ‘worked.’ Work is something hard.”

The secret sauce, according to the former Legler employees I talked to, was Legler’s mixing pot of international people, who kept the company dynamic and creative. “They hired managers and people from all around the world,” Benagli said. “We had managers coming from India, the States, quite a lot from England, from Germany, Switzerland…”

Many called Legler a denim university, which trained up some of the best denim professionals in the world in everything from sales, to dying, and designing. “The people coming out of it were really well trained,” Bonzanni said. Despite being in Italy for a century, the Legler management still hewed to Swiss precision and efficiency, plus Italian creativity, heavily salted with quality control and management techniques Fredy had brought back from a visit to America in the late 1950s.

During those heady days of denim domination, Fredy Legler and his executives and salespeople (including Benagli) lived large, traveling by private plane to meetings and trade shows all over Europe.

As the company moved into the 1980s, denim proved to be the only truly profitable product Legler was making – cotton corduroy was trending down. In 1988, an article in the publication Tinctoria said that there were 1,944 Italian and 406 Swiss employees, with 313 billion Lire in turnover. But it was a fickle success. Others had rushed into Europe, and especially Turkey, to set up denim mills, crowding the market with overproduction. “In the 1980s it had become increasingly clear that investments aimed at reducing costs and making production more efficient were no longer enough,” Fredy Legler’s biography says.

Ideally, Fredy Legler would pass the company on to the fourth generation and let them innovate, but neither his children nor his nieces and nephews were interested in taking over. So in 1989, he sold it to a fellow Italian businessman, Edoardo Polli. The Polli family renovated the old headquarters in the cotton mill in Crespi D’Adda and moved many of the employees there in 1992.

Nobody has nice things to say about Polli. By many accounts, he neglected and mismanaged Legler for the next decade, harvesting money from it without investing anything in its future. “He didn’t buy the mill with the vision to make the mill continue into the next century. He bought the mill to make money,” De Luca said. The company became less international and creative, and more Italian, more provincial. (So says the Italians who worked there.)

It would have taken a committed owner to weather what was coming. The denim industry was rapidly changing, and to Legler’s detriment.

“I worked in Legler in two periods,” Marco Bonzanni explained. “In ‘81 to ‘83, there were very few items, and big volume.” A sample booklet in the Legler archives from that time shows a half dozen dark blue denim fabrics. But then washes and distressing came into vogue. “From the ‘90s onwards, instead of having 20 fabrics in the range, you have 120 for the same size [mill].” The fracturing of the denim orders made it hard for Legler, which thrived on volume, to find efficiencies.

Plus, in the mid to late ‘90s, as the World Trade Organization broke down trade barriers, more low- cost competition came online from Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh and China.

Customers started leaving. “Some of them, they asked for cheaper prices,” Benagli said. “Some of them, they just moved away,” she says. “What can you discuss when you have a 30, 50 percent difference?”

A short-lived partnership with a mill in Pakistan was attempted and abandoned. By 1997, Edoardo had left his nephew Vincenzo in charge of Legler. Vincenzo died at age 37 in 2002, leaving the company without a head.

The company shrank and consolidated. The spinning, weaving and indigo dying operations in Crespi D’Adda were shut down on December 22, 2003, at 4:52 pm, and moved back to Ponte San Pietro. Payroll started coming in late. “It was just down very, very slowly, like a candle, and that was the end of it,” Benagli said. She, Baldi, Cortesi and Bonzanni helped open a partnership for a Legler denim mill in Morocco, but also failed. She finally left in 2007 for another job in cosmetics.

Fredy Legler was not alive to see his family’s firm shutter. After the sale in 1989, he died a year later. His large funeral was attended by fellow Swiss resident Tina Turner, Swiss representatives, and ex-employees.

Legler the company declared bankruptcy in 2008. It was finally liquidated over 130 years after it was first founded.

The Nature of the Business

The family firm Candiani, led by Alberto, scooped up many of the old Legler employees, outlasting the other Italian denim mills to become one of the only remaining in Italy. It produces sustainable denim for high-end and niche denim brands. But it is a rarity in a business that is now laser-focused on lowering costs.

“Brands are led by the bookkeeper,” Bonzanni said. “The bookkeepers rarely have an education in fashion. They work on what gives bigger margins. There are fewer and fewer people who have the passion to understand the product, the process.” He does believe that more thoughtful, committed management could have saved Legler.

“Legler could exist, not at the same level,” Cortesi said.

“Or with headquarters in Italy and production in Africa,” Baldi said.